(ADVISORY: THIS STORY MAY NOT BE ENJOYABLE FOR ANYONE WHO IS SENSITIVE TO HUNTING.)

Saturday, November 2, 1996

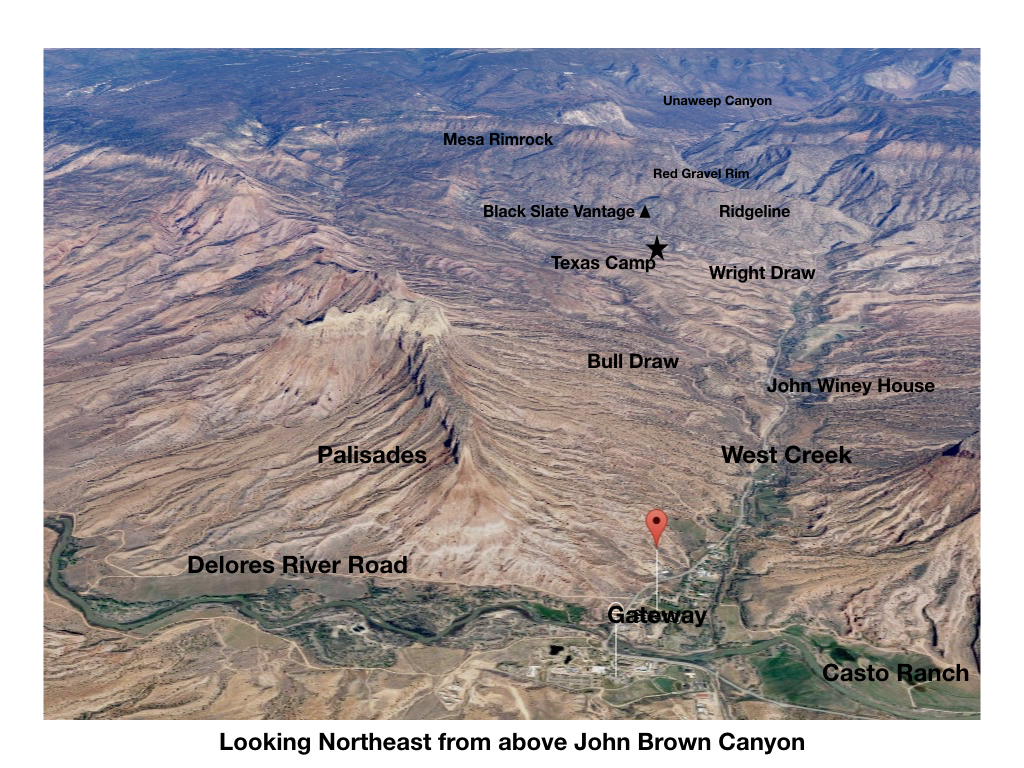

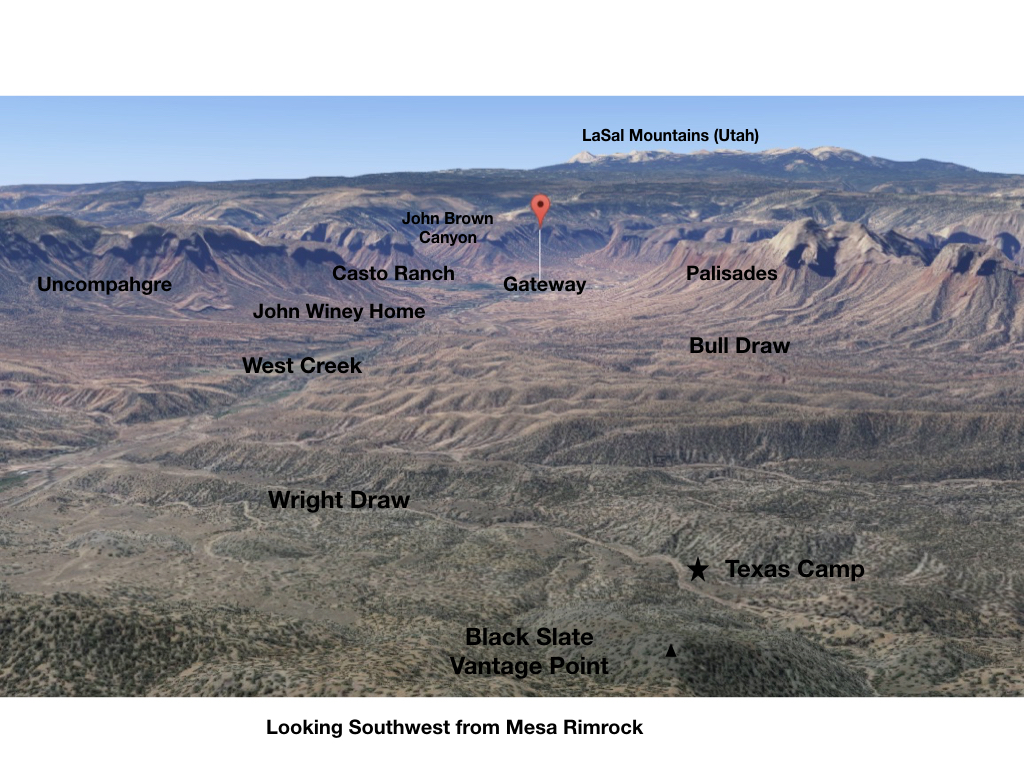

I left camp in Wright Draw at 5:10 am. Climbed the east side of black rock knoll by 6:05 am. Climbed 10 steps; breathed in and out 10 times; climbed 10 more steps.

At 7:30 am, I saw the first deer. It was off to the right about 300 yards down and across the canyon. Suddenly, three more appeared. Now, too many to count. My heart was racing as I desperately scanned each deer for antlers. No antlers, just does, a total of nine. Once spotted, they were easily seen. But, if you looked away for even a second, they would blend into the gravel and rocks and simply vanish. Only to reappear magically with a flick of the ear or a single step.

Two does made their way up and beyond the canyon and over the rim. Others came up the canyon and crossed the red gravel saddle between the black rock knoll and the red gravel rim. Suddenly, two does were within 50 feet on the black slate rock immediately below me. They were following a trail that ran within 10 feet of my vantage spot.

(Previously, I had been scoping the deer looking for horns. It was like an arcade; here’s a deer, find it in the scope, no horns. There’s another deer, find it in the scope, no horns – another doe. Wait, have I checked that one? What about the one to the right?)

Now, I was frozen. The doe was 50 feet away. She didn’t know what I was, but she could sense that I was out of place and didn’t belong. I was motionless. She knew something was different, but couldn’t figure out what it was. Finally, after what seemed like an eternity, she eased silently back down the slate rock and out of sight. I could breath again! I sucked in deep breathes of air and tried to convince my heart to stop pounding as the adrenaline was metabolized out of my veins.

At 8:30 am, another deer appeared in the canyon below. This one was different. I put the scope to my eye and the sun burst into face. All I could see in the scope was the net covering my face and reflecting back off the lens. I jerked my cap and netting off while panic set in!

My next attempt at looking though the scope, fighting the sun, finding the deer. Horns extending past the ears, good deer. I drew in and the gun fired. The deer jumped to the left and ran up the hill toward the rim. Three more shots ran out with no indication of stopping him.

Suddenly, he stopped behind a piñon bush about halfway up the hill. I can’t see him, but I knew he was there. I wait patiently for 30 minutes with my scope fixed on the piñon. My muscles began to ache from being motionless under the weight of the rifle. Finally, the deer stepped out from behind the bush broadside, 250 yards away, uphill. This time, I took a proper rest, put the crosshairs high on his shoulder, took a deep breath, let it halfway out, and squeezed the trigger. The shot ran out and the deer bolted up the hill. I squeezed off another shot as he crossed the rim and out of sight.

Waiting another thirty minutes, I carefully marked the trail followed by the deer on the only paper I had – my Colorado deer license. I meticulously marked each spot where shots had occurred. I stripped down to lighter clothing and prepared to cross the canyon to the deer trail.

As I climbed the hill and reached the location of the first shot – nothing, no hair, no blood, nothing. I continued to slowly climb the steep, red gravel hill; 10 steps, 10 breathes, without any indication that I my bullets had found their target. At the piñon, I saw tracks where the deer had turned back on itself and where the fifth broadside shot was fired. The tracks cut deep into the gravel where the deer bolted up the ridge. I found a small bone fragment, a piece of fatty tissue, and a bit of white hair, but nothing more. Definitely no blood.

I continued climbing toward the top of gravel rim with no additional indication that the deer had been hit. I stopped at a rock outcropping for 30 more minutes to rest and watch for movement. I eased over the top of the rim, I found another small piñon along the deer trail. Underneath the piñon tree, I found a spot of blood about the diameter of a Coke can. Twenty more steps down the trail I found another blood spot; then a third blood spot another twenty yards beyond. Then nothing.

I spent the next two hours walking along the rim and down into the red gravel bowl on the backside. I followed every set of fresh tracks – nothing. I crossed the red bowl at fifty foot intervals without any success. It was impossible to tell which direction the deer went once it dropped out of sight over the rim.

At 1:00 pm, I left the red gravel rim for camp; exhausted, dejected, frustrated. I couldn’t believe that I missed, not once, but four times and even my fifth shot was not a kill shot. When I arrived back at camp, I briefly repeated what had happened, but it was obvious that I didn’t want to talk and no one else wanted to climb the ridge to assist in looking for the deer that would never be found. I ate a light lunch and drank some water, then lay down for about 30 minutes before it was time for the afternoon hunt.

At 2:30 pm, I climbed toward the black slate rock knoll again. I sat silently for the next two and one-half hours bewildered that I may have missed my one and only chance for a Colorado mule deer. At 5:06 pm, I saw several does, but no bucks, coming down the cattle trail that leads from the top of the mesa to the red gravel rim. I hoped and even prayed that the injured buck would magically appear with them, but to no avail. I used a flashlight to walk slowly back to camp. Exhausted.

Sunday, November 3, 1996

I woke dat 4:30 am. David and John had left between 3:00 to 3:30 am to ride four-wheelers to the Delores River Road. Since it was Sunday, I packed my copies of “Experiencing God” and “My Utmost for His Highest” into my backpack. In a previous hunt, I had walked back from the black slate hill and drove to church in the valley on Sunday. However, this time I knew I wouldn’t have the stamina to make two trips up the ridge.

At 5:00 am, I began my climb to the black rock knoll by moonlight. I climbed ten steps and breathed ten times. Occasionally, I would begin to panic and start thinking I wouldn’t get there before daybreak and would forfeit any opportunity to redeem myself. But, when this would happen, I would climb ten steps and breath twenty times. I had learned on a previous trip that the panic attacks were caused by a lack of oxygen due to the altitude and physical exertion. It took a good deal of mental discipline to fight back the panic and slow down until oxygen was restored when every fiber of your body wanted to bolt up the hill.

When I arrived at my vantage point on the black slate hill, I sat down by a dead cedar and scattered my stuff out, keeping it all within arms reach. While it was still dark, I dug into my backpack and put on my long johns and heavy clothes. Clouds began to move in covering the moon and a light rain began to fall. I zipped up my devotionals and other stuff in my backpack, sat on my insulated coveralls, and shivered in the rain. The wind came up and I was forced to put on my insulated coveralls and my last of my layers of clothing.

At 7:30 am, the rain stopped. Nothing was moving. No does, nothing. When 8:30 passed, there was still nothing moving. The rain began again and I moved up the hill under a piñon tree, covered my cope with a leather glove, and tried to keep out of the cold wind.

Sometime later, the rain stopped, the sun came out, and I took off my insulated coveralls when I warmed back up. All too soon, the sun was gone and the cold wind began blowing again. I put on my coveralls for the second time.

At 10:00 am, HE topped the red gravel rim. As he started down the trail, it was obvious that HE was a massive buck – his antlers were well past his ears. HE came right down the hill, running hard, but not pogo sticking. Near the bottom of the hill, where the two trails intersect, HE stopped beside a tree and looked at straight at the black slate hill where I was sitting.

(When he first topped the rim, I began self-talk: wrap the sling around your left arm, take a rest on both knees, put the crosshairs on the deer, aim low if shooting down hill, take a breath, let it half out, squeeze the trigger, see the deer drop out of the scope after the shot is heard and recoil is felt. Don’t take a running shot; wait for him to stop.)

When the buck stopped and looked up at the black slate hill, I took aim low on his left shoulder, let out half of a breath, squeezed the trigger, and watched the deer in the scope as the shot rang out and the recoil was felt.

Initially, he didn’t react to the shot. He ran further down the hill, into the canyon, and almost out of sight. Then, he turned back up the hill toward the rim, stumbled, and fell. But immediately, he got back up and continued down the ravine out of sight. Fearing he would get away, I got up and cut across the black rock knoll to get a better view of the canyon below. Suddenly, I spotted deer running through the cedars and around the knoll to my right. A sick feeling came over me. This deer was also going to get away. The deer disappeared over the knoll before I could see if the buck was among them.

I sat down for a few minutes before deciding there was only one thing to do; go down and check for a blood trail. I shed the heavy clothes and coveralls and dropped over the knoll into the canyon, crossed the ravine, and climbed to the point where the trails crossed. There, beside a piñon tree, I found the spot where the buck had turned up the hill and stumbled. This time, there was blood, lots of blood, and heavy tracks in the gravel. I followed the tracks down the ravine. About twenty yards away, there lay a deer, on it’s side with massive antlers extending well above the body.

I approached cautiously looking for signs of life with my rifle ready to fire. Seeing no movement, I eased closer, dropped the rifle, grabbed the antlers and held on for dear life halfway expecting the buck to come back to life and bolt away. When the buck still didn’t move, I realized it dead and slowly released my grip on the antlers. I pulled hard on the antlers, but could only barely budge the deer. I knew I would have to go back to camp for help, but didn’t want to leave the deer without ensuring it was dead. I didn’t want to ruin the cape by cutting his throat, but also didn’t want to take a chance that he would get away. I eventually field dressed the deer and climbed back up the black slate knoll for the rest of my gear.

As I walked back to camp, I was elated to have killed a nice buck, but I was also exhausted from the events of the previous day. I was simultaneously proud and sadden; proud that I was able to bag a buck, but saddened that such a majestic animal would no longer range freely over the rimrock in Mesa County.

When I reached camp, I told them that I had killed a deer and would need some help getting it back to camp. David and I rode a four-wheeler down Wright draw to the highway, then drove back between the ridges to within about a thousand yards of the ravine. When we walked into the ravine, David was astounded at the size of the buck and antlers. Why hadn’t I told them that I had killed such a massive deer? I really couldn’t answer that question; I guess it was because my parents had such a disdain for pretentious people. Better to simply let others decide for themselves.

I asked David if we could drag the deer down the ravine to the camp. We scouted the area below and found that the ravine plunged over ledge rock that would be impossible to navigate by ourselves, much less with a deer carcass. Our only way out was the way we had come in. We attached a rope to the deer’s antlers, David climbed to the closest piñon tree and snubbed the rope. I would lift the deer up the slope and David would take up the slack. For the next 100 yards, I would lift the deer while David pulled hard on the rope, then would snub it on a piñon tree while I climbed another step up the hill. Eventually, we reached the top of the ravine and dragged the beast another 900 yards along the side of the ridge to the four-wheeler.

On the way back to the camp, we were stopped by the Colorado Fish and Wildlife officer. Once again, my heart sank as I recalled stories of violators losing their game, guns, and vehicles. The officer wanted to check my rifle; I told him nothing the chamber, but the magazine was full, which was legal in Colorado at the time. He checked my deer license; it was properly filled out and attached to the buck. Finally, he simply congratulated me on a nice deer and wished us a safe journey home. Exhausted and relieved, we arrived back at camp with my buck.

Our celebration was short lived; John arrived at camp, congratulated me on the nice buck, and told David and me to get in the truck and head to the river where he had also killed a buck. His deer was about 3000 yards from the roadway toward the Palisades. As we were walking in, we heard and saw some Native Americans hunting against the rimrock that ran to the Palisades. Shortly before we arrived at John’s buck, a shot rang out and we realized they had also bagged a deer. They were probably three times farther away from the road than John’s deer. We began dragging the buck toward the truck; one on the right antler, one on the left antler and one walking behind resting. When we couldn’t pull any longer, we would rotate from right to left to resting. About halfway out, the two Native Americans came walking past us, their buck draped across the shoulders of one of the young men and the rifle being carried by the other. As they walked past, one of them spoke some native words, the other laughed, and they walked on out of sight. I’ve always assumed they were not impressed by the three Caucasians and our ineptness of dragging a deer across the mesa.

Monday, November 4, 1996

Since my hunting was over, I lay in bed until well after sunrise. My body relished the rest. We had skinned both deer that evening and carried the carcasses and heads with capes attached to the local meat locker. They dutifully hung my name on my buck and John’s name on his buck. We made arrangements to pick up both deer on Thursday before we left for Texas.

I eventually got out of bed, cooked some breakfast, then climbed to ridge behind the camp. From my vantage point, I could see down West Creek, across the Dolores River valley, and up John Brown Canyon toward the La Sal mountains in Utah. I found a place to sit among some large rocks on top of the ridge. I sat and read from my devotionals as I watched a snowstorm dust the mesa on the far side of the Dolores River. I was amazed and humbled by a place so stark and enchanting. As I read my devotional, I wondered if it was a hill like this where Abraham offered up his son Isaac or Moses saw the burning bush or Jesus sought a solitary place to pray. My thoughts turned to the magnificent buck and the one that got away and the terrain where they were born and lived out their life. I sat for a long time thinking about life and listening to Garth Brooks on my Sony Walkman cassette player and wondered if the injured buck would be the one the wolves pulled down.

“Wolves”

January’s always bitter

But Lord this one beats all

The wind ain’t quit for weeks now

And the drifts are ten feet tall

I been all night drivin’ heifers

Closer in to lower ground

Then I spent the mornin’ thinkin’

‘Bout the ones the wolves pulled down

Charlie Barton and his family

Stopped today to say goodbye

He said the bank was takin’ over

The last few years were just too dry

And I promised that I’d visit

When they found a place in town

Then I spent a long time thinkin’

‘Bout the ones the wolves pull down

Lord please shine a light of hope

On those of us who fall behind

And when we stumble in the snow

Could you help us up while there’s still time

Well I don’t mean to be complainin’ Lord

You’ve always seen me through

And I know you got your reasons

For each and every thing you do

But tonight outside my window

There’s a lonesome mournful sound

And I just can’t keep from thinkin’

‘Bout the ones the wolves pull down

Oh Lord keep me from bein’

The one the wolves pull down

I didn’t know at the time, but I would only have one more hunt with Jerry, Della, David, John, Henry, and Ed in Wright Draw before my dad would fall ill with Alzheimer’s disease and I would began spending my hunting vacation with my parents on our farm in Missouri. But, at this moment, I simply savored deer hunting in Colorado.